The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), a subset of the IoT evolution, is quite the rage within automation companies as they seek to add a high-margin software component to their traditional businesses. Since Maxim Integrated chips are used to build these automation systems, they get a unique perspective on how automation system design has to evolve or, in some cases, change as companies attempt to put their automation systems online to take advantage of the IIoT. This article briefly introduces the IIoT and focuses on the security challenges that must be solved to implement secure IIoT-capable end systems.

The IIoT in manufacturing

Manufacturing can get the most leverage from the IIoT because of the sheer amount of data it can capture and process; data is the underpinning of the IIoT since it can be analysed and visualised to help optimise operations and costs. Within manufacturing, security solutions provided by intelligent sensors, distributed control and complex, secure software are the glue for this new revolution.

To realise the promise of the IIoT, chip vendors have to put a lot of their systems, including legacy systems, up in the Cloud. This has profound security implications since security implementation for industrial control systems has not kept pace at best and, in some cases, is non-existent. This will change as actors (malicious or otherwise) realise that a factory or a plant is effectively online, and exploit different attack opportunities.

Security will have to be a combination of software as well as embedded hardware to protect critical control systems from a variety of attacks. Three key challenges are: hardware authentication with secure keys, secure communications using TLS and secure boot. Since connectivity (the thing that enables the IIoT) completely exposes all of their security shortcomings, security cannot be an afterthought if they are to realise the benefits of the IIoT.

Benefits of the IIoT at work

A good example of the IIoT at work is General Electric’s newest US$ 170 million plant in upstate New York. It opened about a year ago to produce advanced sodium-nickel batteries used to power mobile phone towers. The factory has more than 10,000 sensors spread across 16,722.5 square metres (180,000-square-feet) of manufacturing space, all connected to a high-speed internal Ethernet. They monitor activities such as which batches of powder form the battery ceramics, how high a temperature is needed to bake these, how much energy is required to make each battery and what local air pressure is being applied. On the plant floor, employees with tablets can pull up all data from Wi-Fi nodes set up around the factory.

Another good manufacturing example is Siemens Amberg electronics plant that manufactures Simatic programmable logic controllers (PLCs). Production is largely automated, and machines and computers handle 75 per cent of the value chain on their own—the rest of the work is done by people. Only at the beginning of the manufacturing process is anything touched by human hands, when an employee places the initial component (a bare circuit board) on a production line. From that point on, everything runs automatically. What is notable here is that Simatic units control the production of Simatic units. About 1000 such controls are used during production, from the beginning of the manufacturing process to the point of dispatch.

The IIoT harnesses sensor data, machine-to-machine (M2M) communication and automation technologies. Smart machines are better than humans at accurately and consistently capturing and communicating data used to fix inefficiencies and solve problems in terms of up-time, scheduled maintenance, power efficiency and more efficient utilisation, sooner.

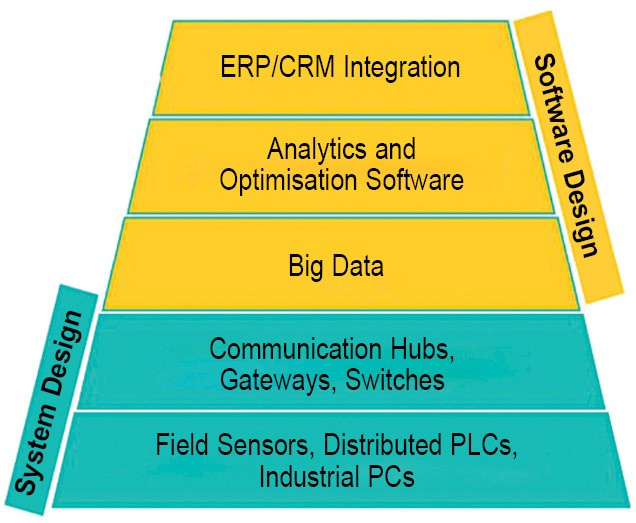

Maxim Integrated has broken down the IIoT in terms of a stack as shown in Fig. 1. At the very bottom of the IIoT stack, they have the devices (systems) on the factory or process floor. These can be field sensors, controllers, industrial PCs and so on. All of these are hardware systems and can include aspects of hardware security. These end devices must have useful data to communicate and are generally hooked up to communication hubs, gateways and switches so that data can be put in the Cloud (or an intranet) as Big Data.

But that is not all. The promise of the IIoT is that this data can be integrated within the ERP and CRM software of the firm to not only efficiently plan and cost out a manufacturing process, but also to use customer/market information to change assembly lines and process parameters.

The top of the stack impacts software development and integration, whereas the bottom impacts the system design perspective.

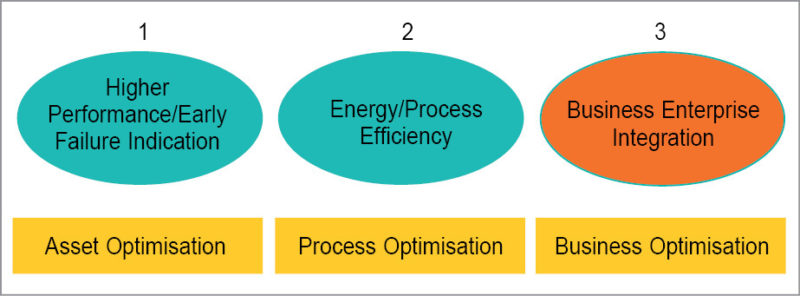

Primarily, the benefits of IIoT can be broken down into three groups (Fig. 2): asset, process and enterprise optimisation. It is easier to optimise a motor than it is to optimise a drilling operation, which, in turn, is easier to optimise than the manufacturing lines of a large enterprise. But optimising at every level is the dream of the IIoT.